Anatomy of Pepin County

A Traffic Safety Summary

Introduction

This document was created by the Division of State Patrol Bureau of Transportation Safety and Technical Services (BOTSTS). The data is based on three-year (2018 - 2020) trends.

The intention of this document is to assist Traffic Safety Commissions to examine their own transportation safety issues within their respective county and to identify potential countermeasures. While these crash and driver behavior trends are examined at the county level, these trends can be examined at a more local level. BOTSTS can provide this analysis and data to your local municipality.

For requests, email BOTSTS at CrashDataAnalysis@dot.wi.gov.

Zero in Wisconsin

WisDOT has adopted Zero in Wisconsin, the belief that no one should be killed or seriously injured from using the road network. The aim of Zero in Wisconsin (otherwise known as Safe System, Vision Zero or Sustainable Safety) is for a world free from road fatalities and serious injuries.

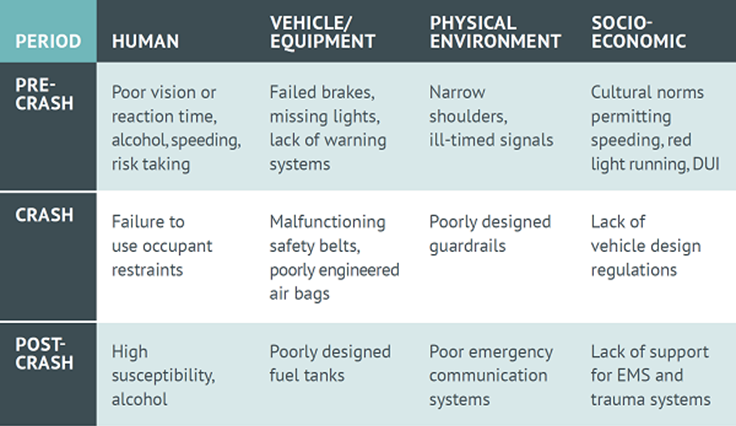

The Haddon Matrix (below) models basic principles to be applied to safety analysis. Each cell of the matrix represents a different area in which countermeasures can be implemented to improve traffic safety. Countermeasures applied to the pre-crash phase are designed to reduce the number of crashes. Countermeasures that are applied to the crash phase would not stop the crash, but could reduce the number or severity of injuries that occur as a result. Countermeasures focusing on the post-crash phase optimize the outcome for people with injuries, and prevent secondary events. Learn more about this approach at the Federal Highway Administration and Zero in Wisconsin.

Crash Trends

Per year in Pepin County, an average of

|

While |

| 139 drivers are involved in a crash |  |

|

October has the highest number of crashes |

| 33 people are injured |   |

|

October has the highest number of injury and fatal crashes |

| 2 people are killed |  |

| Where | 6 out of 10 injured or killed people are Pepin County residents |

|

|

| 5 out of 10 fatal and injury crashes occur on a county or state road | 15 out of 20 injured or killed people are Wisconsin residents |

| When | |

|

|

| 2pm-3pm is the peak time for injury and fatal crashes |

Heat map of all crashes (2018 - 2020)

Explore crash hotspots in your local community in Community Maps. If you work for a public agency, you may request a log-in to gain access to advanced search and analysis capabilities.

On an average year in Pepin County, Friday has the highest number of injury and fatal crashes. In addition, over a 24-hour period, injury and fatal crashes occur most frequently between 2pm-3pm peaking at 3 crashes in total throughout the year.

| Crash Type | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Injury | 30 | 32 | 21 | 21 | 32 | |

| Property Damage | 111 | 102 | 102 | 84 | 68 | |

| Total | 142 | 134 | 125 | 105 | 103 | - |

Here are trends of fatal, injury, and property damage crashes over the past 5 years.

Crashes on State roads are disproportionately represented in injury and fatal crashes. On roads with higher posted speed limits, there’s a higher risk for a severe injury or fatality if a crash were to occur.

Commuting Flows

Place of Residence

Place of Work

Total workers that work in Pepin County:²

2,810

Of these, 66% also live in Pepin County

Place of Residence

Place of Work

Total workers that live in Pepin County:²

3,578

Of these, 52% also work in Pepin County

Locals are more likely to be involved in a crash in Pepin County as opposed to visitors. 55% of occupants injured or killed in a crash in Pepin County also live in Pepin County.

Transportation Safety

Alcohol and Drug-Impaired Driving

In Pepin County, 6 people are injured or killed in a crash involving a driver believed to be impaired by drugs or alcohol, in an average year. That is 40% of all persons killed in a crash. Statewide, this is 33% of all persons killed.

While 69% of drivers believed to be impaired by drugs or alcohol are male.

Hotspots of alcohol and drug-related crashes with an injury or fatality (2018 - 2020)

Distracted Driving

In Pepin County, a driver being distracted is listed as a contributing factor in 16% of injury and fatal crashes. Statewide, this is 12% of injury and fatal crashes. Distracted driving is based on a two-year (2019-2020) trend due to a change in data fields. Below shows the breakdown of the factors in these distracted driving crashes.

Occupant Protection

Statewide seatbelt usage has been increasing over the past two decades. This past year experienced a usage rate of 89.2%, which is based on an annual seatbelt survey. Occupants not wearing a seatbelt are more likely to suffer a serious injury or fatality. Of the total statewide occupant fatalities, 1 out of 3 were not wearing a seatbelt. Statewide seatbelt usage rate reached an all time high in 2019.

People in your community can conduct their own seatbelt survey via the ‘Local Seatbelt Survey’ in the app store.

Bicyclist and Pedestrian Safety

In the last 3 years in Pepin County, 0 cyclists and 0 pedestrians were killed or injured in 0 crashes. The below two bar charts shows the contributing factors and where these crashes occurred.

A bike or pedestrian crash is more likely to happen in an urban area, however, a fatal or serious injury crash is more likely to occur in a rural area due to higher speeds and due to further distance from a trauma center.

Locations of injury and fatal bicycle crashes

Locations of injury and fatal pedestrian crashes

Motorcycle Safety

In the last 3 years in Pepin County, 23 motorcyclists were killed or injured. Of these, 59% were not wearing a helmet.

Locations of injury and fatal motorcycle crashes

The type of helmet and other safety equipment worn, such as protective gear and gloves, can also impact the type of injury sustained.

19 motorcycle drivers were involved in a fatal or injury crash. 47% were Wisconsin drivers. Of these, 22% did not have a valid M endorsement.

Teen and Older Drivers

In Pepin County, teen or older drivers make up 24% of drivers involved in a fatal or injury crash. Statewide, this is 19% of drivers in fatal and injury crashes.

Breaking this down for Pepin County:

13 teen drivers make up 9% of drivers involved in a crash and make up 4% of licensed drivers and

21 older drivers make up 16% of drivers involved a crash and make up 27% of licensed drivers.

Locations of injury and fatal crashes involving a teen driver Locations of injury and fatal crashes involving an older driver

Lane Departure Crashes

More lane departure crashes occur in Pepin County, out of total injury and fatal crashes, compared to the state. That is an average of 15 fatal and injury lane departure crashes per year. Colliding with a Ditch/Culvert was the most frequent first harmful event. Breaking this up, 87% are single vehicle only, while statewide 75% are.

A lane departure crash is defined as when the driver crosses the centerline, edge line, or leaves the roadway and then usually colliding with another vehicle or an object, such as a guardrail or a tree. The cause of a lane departure crash could be a mixture of factors – speeding, being impaired by alcohol, or feeling tired.

Below shows the breakdown of the first harmful event in these lane departure crashes.

Speeding

Speeding includes both exceeding the speed limit and driving too fast for conditions. Speeding has a compounded affect in a crash; decreasing speed can reduce the crash risk, reduce injury severity, and make it possible to control the vehicle if an event were to occur. Of all fatal and injury crashes, 29% involved speed as a contributing factor resulting in 10 fatalities and injuries in an average year. Statewide, this is 20% of fatal and injury crashes.

Comparing to road type by lane miles, State roads are the most disportionate road type for fatal and injury speed crashes.

| Crash Type | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Injury | 8 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 | |

| Property Damage | 22 | 20 | 16 | 12 | 18 | |

| Total | 30 | 28 | 22 | 21 | 26 | - |

Here are trends of all speeding-related crashes over the past 5 years.

1 out of 4 of all crashes where speed is a factor involves a young driver.

Hotspots and analysis areas of all crashes involving a speeding driver

Appendix

Predictive Analytics

Predictive Analytics is an emerging program that uses established crash trends to identify “hotspots” in a particular locality. The program is geared to promote changes in driving culture in and around crash hotspots, with a particular focus on outreach. Utilizing a Safe Systems Approach, Predictive Analytics introduces multi-pronged solutions that involves a wide array of partners and stakeholders in traffic safety working together to reduce injury crashes.

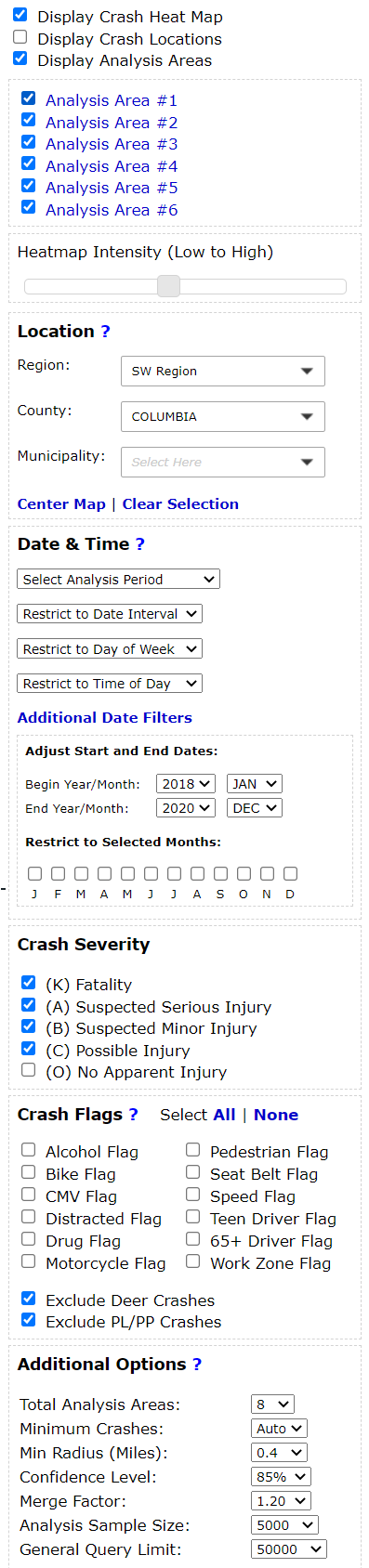

Hotspot Selection

A county or municipality may use whatever method they decide to select their own hotspots. But utilizing Community Maps, a jurisdiction can target areas that have a demonstrated history of injury crashes. For example, using the search components on the left give us the following map, with several hotspots to choose between:

If there is a specific issue area that a locality wants to focus on (such as impaired driving or speeding), consider using specific crash flags when generating hotspots.

Urbanization

Pepin County is located along the Mississippi River and Lake Pepin, separating it from the state of Minnesota. The entire county is rural. Pepin County is adjacent to the Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington and the Eau Claire metropolitan areas and is adjacent to the Menomonie urban cluster.

Vehicle Miles of Travel (VMT)3

A crash rate of ^

VMT is a measure of the total amount of and distance of vehicle travel in a year.

In Pepin County, the 2019 VMT was 108 million with a crash rate of 24 injury and fatal crashes per 100 million VMT, lower than the state’s rate of 42.

^Crash rate as measured by total injury and fatal crashes per 1 million vehicles miles traveled in 2019

Grants

The State Patrol Bureau of Transportation Safety and Technical Services (BOTSTS) administers federally funded overtime traffic safety grants to county task forces each year. A county task force is a group of law enforcement agencies working together to plan high visibility enforcement in their communities.

The overtime grants are awarded to agencies in task forces using a data driven targeting process. The targeting process includes a review of crash data from previous years to determine what areas have a traffic safety problem. The process is used to determine locations of concern in the areas of impaired driving, speeding, and unbelted vehicle occupants.

To save lives and reduce injuries by preventing traffic crashes, BOTSTS, in partnership with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), sponsors campaigns that mobilize hundreds of law enforcement agencies throughout the state to increase motorists’ compliance with traffic safety laws. The high-visibility law enforcement efforts are combined with effective media campaigns to get more motorists to buckle up, slow down and drive sober. The national mobilizations are Click it or Ticket and Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over.

| Agency | 2018 Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over - Winter Holidays | 2019 Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over - Labor Day | 2019 Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over - Winter Holidays | 2019 Click It or Ticket | 2020 Click It or Ticket | 2020 Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over - Labor Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durand PD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pepin County SO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pepin PD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No agencies participated in any task forces.

Abbreviations: DPS = Department of Public Safety, PD = Police Department, SO = Sheriff’s Office

Health Impacts and Medical Costs

Compared to Wisconsin, fewer people are in a crash in Pepin County (per 1,000 residents)4

and fewer people are hospitalized due to a crash (per 100,000 residents)4

While average medical costs per hospitalized person4 is higher

and fewer people died4 out of all occupants.

.

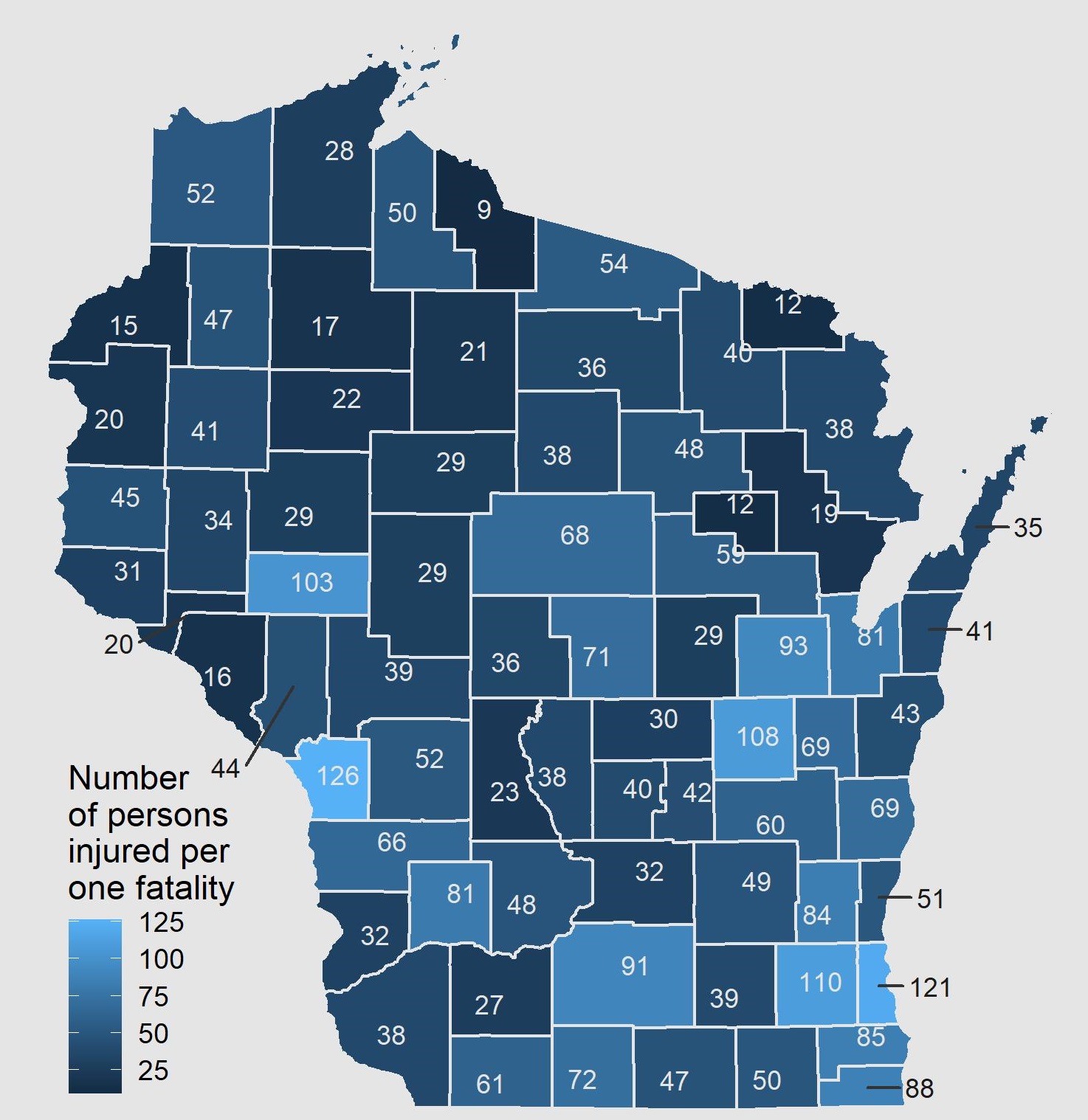

Injury-to-Fatality Ratio

In Pepin County, for every 20 people injured, 1 person is killed. This is the injury-to-fatality ratio and is below average from Wisconsin where the ratio is 66 to 1.

The injury-to-fatality ratio is computed by dividing the total number of crash injuries by the total number of crash fatalities. A higher ratio is more ideal since fatalities comprise a smaller proportion of total crash victims. The ratio tends to be lower in rural areas where there’s a higher proportion of county and state roads. Higher speed limits means higher crash injury severity. Also rural areas generally suffer from a longer distance to hospitals and fewer emergency response services.

Sources:

1Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Received from K. Spencer. Dec. 3, 2019. wisconsindot.gov/Documents/projects/data-plan/veh-miles/vmt2016-c.pdf

2United States Census Bureau. 2011-2015 5-Year American Community Survey Commuting Flows. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2015/demo/metro-micro/commuting-flows-2015.html Accessed Oct. 11, 2019.

3Wisconsin Department of Transportation. “2019 Vehicles Miles of Travel (VMT) by County.” Accessed May 20, 2021. https://wisconsindot.gov/Documents/projects/data-plan/veh-miles/vmt2019.pdf

4University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for Health Systems Research & Analysis. Wisconsin Crash Outcome Data Evaluation System Project. 2013 - 2017. https://transportal.cee.wisc.edu/products/CODES/default.htm Accessed Oct. 11, 2019.